You might know Lo Carmen as Loene Carmen, the name she used until 2012.

You might know Lo Carmen as Loene Carmen, the name she used until 2012.

If you’re like me, you’ll know her primarily as an actress.

Plucked from Kings Cross pizza bar obscurity to star as Freya in The Year My Voice Broke (1987). Her astounding, compelling performance as Sallie-Anne Huckstepp in Blue Murder (1995). And wasn’t she in Red Dog (2011)?

I had only a vague awareness that she was also a musician, a singer/songwriter. And that Aden Young was her partner.

I had no idea of her family history, nor her place in the networks of creative artists, nor her intersections with my own life.

And I certainly didn’t know she could write like this.

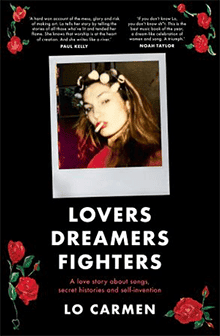

Lovers Dreamers Fighters is a multi-layered book – and a great read.

One one level, this is a memoir of an Australian woman and creative artist in the late 20th to early 21st century. Growing up in a creative, free-thinking family, regarded as an eccentric at school, heading out on her own from Adelaide to join her father at Kings Cross at 13, getting the big acting break at 16, being part of a generation of actors and artists who continue to shape Australia’s artistic footprint today, finding herself as a songwriter and musician and, ultimately and significantly, staying true to the idea of art being art for its own sake. It’s a compelling portrait of someone who crafts something resembling a career from an adamantine commitment to artistic values. I mean, imagine being Loene Carmen, auditioning for a “Loene Carmen type role” and getting knocked back.

The way Carmen constructs her personal history is to profile the artists and performers who influenced her along the way, from her earliest years to most recently. Her primary focus is on women who achieved great art despite the discrimination they faced, the physical and mental torture some of them endured, the dismissal of their talent and their inability to make a decent living. One thing I found fascinating is that I “knew” the stories of all of these women, they’re well known in that sense. What I didn’t expect is that in Carmen’s telling, I found out things about each and every one I had not known before: details of their lives that are often shocking and distressing. Carmen goes deep and hard.

As Carmen reflects on her years at Kings Cross in the early 80s, she notes that Sallie-Anne Huckstepp, who she would go on to play in Blue Murder in the mid-90s, walked those same streets as teenaged Loene waved to the spruikers on her way to get chips from the Chicken Spot. She may well also have seen me and Ian Pidd busking outside the Chicken Spot. One of the things we did successfully was to gather a crowd, and it didn’t take long before some of the “spruikers” very politely asked if they could “work our crowd”, handing out flyers for their night clubs. Of course, we agreed, and when some of Chicken Spot staff later threw chips at us, the spruikers … um, convinced them to stop. It’s unnerving to think among the bystanders to these scenes could have been Sallie-Anne and the 13 year old who would later play her.

This touches on both one of the strengths of this book, and a possible weakness. Of the five famous Australian women Carmen profiles, she has personal connections to all of them. She delved deep into the life, times and family of Sallie-Anne in order to produce a bravura performance as the murdered sex worker, police whistleblower and advocate. Her band opened for Renee Geyer, who gave her advice on stage performance. Robyn Archer started out as part of her father’s band. She was Vince Lovegrove’s secretary when he was managing the Divinyls and she hung out with Chrissie Amphlett. She also became close to Suzi Sidewinder and her son with Lovegrove, Troy, who both died from AIDS-related illnesses. A 10 month old Loene was backstage when Wendy Saddington rivetted the audience at Adelaide’s Myponga Festival in 1971, and it was her father who revived Saddington’s singing career in the early 80s. That’s a pedigree of artistic association very few people can match.

In one way or another, Lo seems to know everyone, which is pretty unusual, even in the highly interconnected, often incestuous and nepotistic world of Australian arts. It does give her great and immediate insight but it also places her outside the average reader’s sphere of reference. Maybe she was aware of this and thus deliberately set out to back up her personal recollections with meticulous research, all thoroughly referenced and indexed. She’s not making this stuff up, and she can prove it. And she certainly doesn’t trade on these associations, she hangs on to a sense of being an involved observer.

Robyn Archer gives Carmen the chance to also delve into the lives of the some of the 11 women Archer portrayed in her cabaret A Star is Torn, including Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Edith Piaf, Judy Garland, Marilyn Monroe, Patsy Cline, and Janis Joplin. This is a double whammy for Carmen – she gets to reflect on the tortured, impassioned lives of a set of female singers and actors who, despite being well known, are largely underestimated, misunderstood, and trivialised, if not forgotten – through the lens of one of Australia’s greatest performers almost magically conjuring them up on stage, herself not really held in the high regard she should be. I was lucky enough to see A Star is Torn in the early 80s – an astonishing, eye-opening show created by one of our greatest ever performing artists.

One of the most moving profiles is of Carmen’s grandmother Pat, a teenaged single mother in 1945 who was forced to give her baby up for adoption. Both an indictment of the ignorant and harmful social policies and attitudes in Australia before and after WWII, and a paean to the strength of independent women and the prevailing bonds of family, this lets Carmen reflect on her own development as a woman, a mother, a partner and, inevitably, an artist.

Men do get a look in. Carmen’s father, Peter Head, provides a strong anchor throughout as someone committed to life as a musician while holding on to deep values based around art, love and family. Kris Kristofferson comes out as a sensitive, committed and supportive artist who followed his own dream and had it come true. There are cameos from Martin Sharp, Tiny Tim, John Cann, Vince Lovegrove, and much less flattering appearances from Roger Rogerson, Harry Bailey and Billy Snedden. And there is Aden Young – Carmen is not waylaid into a diversion about how true love found them and they came together – that’s a Women’s Weekly article, out of place here. But we do get a sense that they built something together that has lasted to this day, “A couple of abstract loners. We get each other …”

One of the little delights in this book is Carmen’s occasional listing of the quirks of artistic life. She happily points out many instances of later successful artists being rejected, accidents and muckups that were kept and came to define a piece of work, unlikely collaborations and hidden connections. These snippets are delivered straight up, in a matter-of-fact narrative style – no exclamation marks, thank you, and no dot points.

All in all, Lovers Dreamers Fighters is a terrific book. By highlighting the often terrible experiences of the women who have inspired her, Lo Carmen builds a highly evocative portrait of them and of her own development as an independent woman, a mother / partner / daughter and a committed musician / singer / songwriter / actor. Without intending to, she also makes herself a role model for today’s young women. I hope Augusta reads this book.

Yes, now I’m going to read it! Great review, bro!