Reviewing creative works by friends can often be tricky. You don’t want to be overly gushing, even when the work is obviously great, because people will think you’re just being nice to a friend. And then it’s also easy to slip into being unreasonably critical, which may well endanger your friendship, especially if you make your review public.

Reviewing creative works by friends can often be tricky. You don’t want to be overly gushing, even when the work is obviously great, because people will think you’re just being nice to a friend. And then it’s also easy to slip into being unreasonably critical, which may well endanger your friendship, especially if you make your review public.

If you want to know more on how I know Mary-Lou, see my previous post.

Luckily, in this case, I don’t think I have to worry on either front.

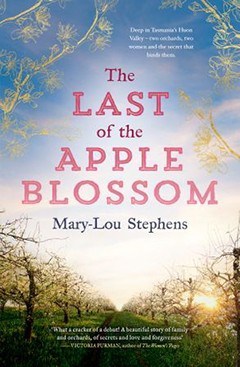

The Last of the Apple Blossom is a wonderful book and, I think, an important one.

It operates on several levels at once without ever losing its focus or any clarity.

It’s an account of a complicated history of family relationships from 1967 to 1976, although it references previous history, has two more chapters in 1985 and adds a coda set in the present day to wrap things up.

It’s a social history, documenting how an industry, a community and several generations of people are forced to evolve rapidly in a period of upheaval and change.

It’s a romance, a tale of deep passions lit, cooled, thwarted and consummated.

And on top of all that, colouring all of those, it’s a record of and a love letter to southern Tasmania.

I can’t overstate Stephens’ beautifully detailed evocation of the specific physical character of the Huon Valley and its surrounds. In what seems like a few strokes of her pen, she brings to life the towns, roads, hills and bays that are familiar to anyone who has driven south west from Hobart to the Huon. I haven’t thought of that mountainous outline we called Sleeping Beauty for many years but it was instantly clear to me and achingly familiar.

It’s fair and in no way a diminution of her work to say that I have the fortune of knowing very well every place depicted in the book. That simply lets me attest to the truth of Stephens’ writing. My first paying job was on my brother’s book stall at Salamanca Market on Saturday mornings in 1975, and she expertly describes not just what that looked like, but what it felt like. The gap left from the Tasman Bridge disaster that same year is mentioned only in passing but locks the reader instantly in time and place.

The specificity of the locale is not always explained but it doesn’t have to be. To my knowledge, Tasmania and the ACT are the only places in Australia where public high school students move on after Year 10 to a separate matriculation college. But when a teenaged character says, “… what’s the point of going to matric if I’m not going to uni?” the context makes the meaning perfectly clear.

At the same time, I learned so much from this book. Like any local, I was aware of how important the apple industry was to Tasmania during my childhood but I’d not previously understood just what a devastating impact events like the bush fires of 1967 or Britain’s entry into the European common market in 1973 had on it. Stephens has clearly undertaken a lot of research into the apple industry and orcharding, and it shows in her characters’ understandings, words and actions. And now I really want to know what a Gravenstein tastes like.

Now that I’ve mentioned them, I also have to give Stephens great credit for her description of the fires that open the book. She captures in excruciating detail the impact, the drama, the fear and the horror felt by those who lived through those February fires and their aftermath – right down to the sense of how much worse it could all have been but for sheer luck. I’m sure that people who have experienced any of the terrible fires like Victoria’s Black Sunday or south coast NSW in 2019-20 will agree that Stephens gets this tremblingly right.

I suspect that Stephens’ experience as an actor has played a part in how well she inhabits her characters’ skins and conveys their foibles, from young children to old farmers. In less confident hands, especially the central four characters could easily blur into one another, but Stephens keeps them clear and distinct even as they hide from and reveal things to each other. Supporting characters from surfer boys and haughty grandmothers to lesbian hippies circle round, adding colour, depth and perspective without ever taking the focus fully away from the two central couples.

I won’t say too much about the plot because a great deal hinges on sudden twists and unexpected revelations. Often, the reader knows something is coming but what it exactly is still takes us by surprise. I’ll also say that it takes a confident and adept writer to attempt physical love scenes in print but Stephens handles them masterfully, her deft and poetic words never straying into either raunch or prudishness. No bodices were ripped in the making of this novel.

If there’s an author I was most reminded of with this book it’s John Steinbeck, who similarly folded very human stories with social and historical scale and scope in novels like East of Eden and The Grapes of Wrath. Like those books, The Last of the Apple Blossom is highly cinematic, and I can think of directors and actors who could turn this into wonderful film or television.

I fully expect The Last of the Apple Blossom to feature in major literary awards, assuming her publishers enter it. While that may be unusual for a first-time novelist, this is not a novice-level book. I think it will stand up over time as a major work of Australian literary fiction.

If that’s overly gushing, so be it. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

Yes yes yes!! D❤️X