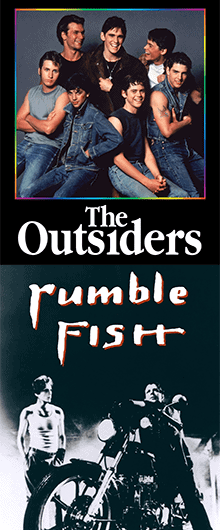

This is a great double bill.

This is a great double bill.

In one sense, it’s an obvious one. Both movies are based on books by S.E. Hinton. She wrote The Outsiders when she was 16 and was just 18 when it was published in 1967. The book has since gone on to be fairly called a classic of American young adult literature, and it rightly appears on many lists of the greatest books of the 20th century.

Its subject matter, a family of three brothers in city very much like Tulsa, Oklahoma who become embroiled in gang warfare with deadly results, means it is still found on lists of books banned by US schools for its portrayal of youth drinking, smoking and fighting, which only adds to its lustre as a book kids want to read. The cult status of The Outsiders is perhaps best summed up by the house used as the movie’s setting having been bought by a fan and turned into a museum.

Rumble Fish is also based on a Hinton book, this one published in 1975. It’s about a disaffected teen whose brother, known only as The Motorcycle Boy and idolised as a gang leader, has been mysteriously absent for some time. Rusty James aims to emulate his brother’s status, even though his brother famously called a stop to gang warfare before he disappeared. Significantly, their mother left the family, an action their alcohol-dependent father comes to defend.

The stories in the two books are not connected but they share vivid portrayals of youth culture in urban environments, and they don’t shy away from teenage drinking, smoking, sex, and violence.

The movies based on these books were made in 1983, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, who credits a school librarian and her students’ petition as the inspiration for taking on The Outsiders. While making that film, Coppola decided to use many of his cast to make Rumble Fish, as well, more or less on their days off. Having worked together on the screenplay for The Outsiders, Coppola and Hinton also collaborated on Rumble Fish.

So, there’s a clear synthesis between these two movies. However, what makes this a truly extraordinary double bill is that the end results of the two film projects are so very different they actually become a study in contrasts.

Where The Outsiders is shot in a fairly straightforward fashion, designed to appeal to a young audience and letting the content of the story be its innovation, Rumble Fish is an exercise in pushing the filmic envelope, as unusual an American 1980s movie as can be imagined.

Key aspects of The Outsiders are its unflinchingly truthful portrayal of youth culture, its emotional intensity and what turned out to be an extraordinary cast. That cast includes – before they were stars – Patrick Swayze, Rob Lowe, C. Thomas Howell, Matt Dillon, Diane Lane, Tom Cruise, Ralph Macchio and Emilio Estevez. Throw in Tom Waits, Leif Garrett, a very young Sofia Coppola, an uncredited appearance by Melanie Griffiths and a cameo by Hinton as a nurse, and you have a movie buff’s dream.

Apart from this cast being the beginning of what became the Brat Pack, there are many anecdotes from the making of The Outsiders, from the litany of practical jokes on the set to Tom Cruise have a tooth dentally removed to replicate the result of a gang fight.

The story is one of a family trying to stay together as a unit (the boys’ parents are dead) within the larger context of the gang family, set against social, educational and law enforcement frameworks not designed to support them. The humanity of the teenage characters is emphasised and events bring to light both their strength and their fragility. In this, Hinton and Coppola tapped into something deep and truly meaningful.

Matt Dillon and Diane Lane also play lead roles in Rumble Fish, but are joined by another amazing cast list, with Mickey Rourke, Dennis Hopper, Nicolas Cage, Chris Penn, Laurence Fishburne, and Vincent Spano. Tom Waits gets a slightly bigger role, as does Sofia Coppola, and Hinton re-appears, this time as a prostitute.

I mentioned that Rumble Fish was shot very differently from The Outsiders, and this is where it gets really interesting. Coppola decided to film the story in black and white, with one very notable exception. The title refers to Siamese fighting fish kept in a pet store, which are stored in separate aquarium cells so they don’t attack each other.

The Motorcycle Boy is convinced they wouldn’t fight if they were released into the river and had room to co-exist. To highlight the metaphor, Coppola decided to show the fish in colour, the iridescent blues, reds and yellows creating a striking contrast to the rest of the black-and-white film.

Beyond that, Coppola chose an equally striking cinematographic style, full of shadows and angles and reflections, somehow simultaneously evoking German expressionism and French new wave impressionism, with a strong dose of Citizen Kane-era Orson Welles thrown in.

The performances are equally art-house, with odd conjunctions of mumbling, shouting, background dialogue and portentous silences. Matt Dillon comes across as (even) more affected than in The Outsiders, while Mickey Rourke is in his element as The Motorcycle Boy: enigmatic, self-contained, threatening, and ultimately disappointed in life.

It staggers me to think of these two casts working more or less simultaneously on two sets on two films steered by the one director and author. Coppola, of course, was coming off The Godfather Parts I and II, The Conversation and Apocalypse Now, and could probably do whatever he wanted and attract quality actors.

That makes it all the more extraordinary that he chose to work on two “youth” films with casts of lesser known actors, one of which was a stylistic anomaly, as far from Hollywood as it’s possible to get. Coppola’s dedication of Rumble Fish to his own big brother August hints that he brought a very personal perspective to that movie.

As a final point of distinction between these two so-similar yet so-different movies, the soundtrack of The Outsiders is dominated by Elvis Presley songs, orchestral incidental music by Carmine Coppola and a theme song by Stevie Wonder. Rumble Fish, on the other hand, has a soundtrack of percussive, discordant, dramatic and sometimes uncomfortable music from Police drummer Stewart Copeland, with the theme song “Don’t Box Me In”, written by Copeland and sung by quirky Wall of Voodoo singer Stan Ridgway.

I read and loved the books before these movies were made, and they stand up for me as rare examples where the filmic versions not only bear out the strengths and values of the books but add another dimension. To watch them one after the other is a very special treat.

Thanks for reminding me of these 2 Great Classics **

Time to watch them – yet again . . .