The more I think about it, the more I understand how who I am now has been shaped in significant ways by my school days.

I’ve remarked elsewhere about how Abbotsfield Primary School shaped me. When my family arrived in Australia in 1965 they were advised that, as I was not yet five years old, I would be enrolled in kindergarten, regardless of the fact I had already spent a year in kleuterschool in my home town of Leeuwarden (that’s me in the blazer).

When my mother told me about this in later years, she felt there was a certain patronising attitude toward the Dutch education system, so that my year in kindy didn’t really count. This would turn out to be quite ironic.

So, I repeated kindergarten, which was fine as it allowed to acclimatise and learn English in a more play-oriented setting rather than a formal learning context.

As I moved on through the infant classes at Abbotsfield Primary, I thrived, excelling in all my subjects. By Grade 3, my report card shows A++ in all subjects except maths, in which I recorded a mere A.

As a result, and with the awareness I had repeated kindergarten (hah!), my parents were advised I would be skipping Grade 4 and go straight to Grade 5.

Instantly, I became the youngest in my class but soon showed I was totally capable of stepping up.

Marks in all my subjects continued to be consistently high, the best in my class, rivalled only by the beautiful and athletic Sally Lansky. Our academic rivalry was the subject of great interest among both students and teachers.

One area where I had it over Sally, though, was in drama. Even in infant school I had shown considerable potential, having scored the key role of Joseph in the Grade 3 nativity play. Not bad for a wog kid.

By Grade 6, I was one of the more experienced and confident 10 year old actors around. I won the challenging role of the killer judge in the end of year play, Ten Little Niggers (before it was bowdlerised into Ten Little Indians, which actually doesn’t sound much better now).

I had no trouble learning all the lines, something I think was a byproduct of my prodigious reading as I’d learned to speak English.

I did, however, have trouble conjuring up a sufficiently loud and evil cackle from the wings as the climax approached. Mr McCulloch, our headmaster, stood beside me and deputised vocally, which I think he rather enjoyed.

I even managed a fairly decent mid-air twist as I was “shot” by the hero (you try it, it’s not easy).

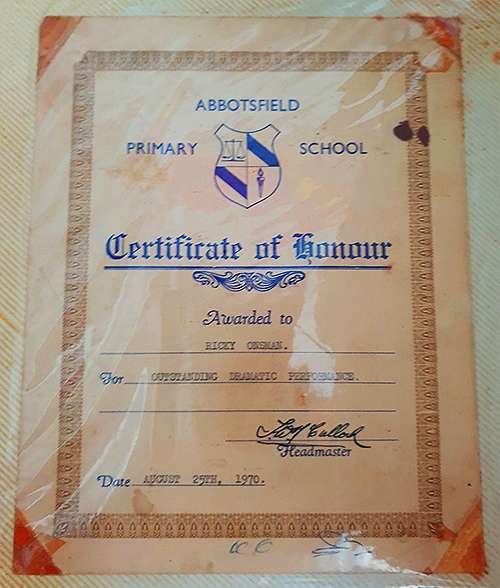

For this effort, I was rewarded at the end of year school awards ceremony with a Certificate of Honour for Outstanding Dramatic Performance and it was clear that I was set for acting glory.

I was also awarded a second Certificate of Honour for Outstanding Academic Achievement that year, my last at Abbotsfield Primary.

If I recall correctly, only Sally Lansky (of course) equalled this achievement, with twin Certificates for Outstanding Academic and Athletic Achievement.

And so I moved on to Claremont High School.

Secondary education in Tasmania was in transition during my time at CHS. When I started, I was in E Class. By the time I left it was from Year 10. Subjects changed – by name, at least – such as Social Studies evolving into Social Science.

I think this had something to do with classes being streamed rather than arranged by alphabetical order of student surname but frankly it was never explained to me.

During each of my four years at Claremont High, the school had about 1,500 students, a very high number for a public school in the suburbs with limited resources, with class sizes typically over 30.

The student intake from the surrounding area was dominated by the children of workers at the nearby Cadbury’s chocolate factory, which included both my parents.

This included a great number of migrant families, almost entirely from the UK and Europe. My school friends were mostly English, Irish, Scottish, Greek, Italian, Polish, Swiss, German, Yugoslav and Turkish.

Even though they were heavily outnumbered, the Australians – that is, those who had been here for more than a generation and spoke with an Australian accent – were culturally dominant.

To say it was a rough school, is to mince words. It was a hotbed of racism, sexism, and bullying – a training ground for junior criminals. During my time, there were several rapes on school grounds, regular gang fights and students frequently disappeared as they were expelled or transferred to reform schools.

Don’t think that I’m exaggerating. With hindsight, I’m shocked at what was considered normal.

I was present when a beefy senior student who was already shaving punched out a much smaller male teacher, who resigned after he came out of hospital and we later learned had become a monk. The student was expelled.

Claremont High School teachers, perhaps understandably, became as tough and cynical as their students. Blackboard erasers were regularly thrown at misbehaving student heads. Detentions were issued with abandon. Caning was frequent. Any hallway would be likely to have a student standing outside at any time, banished for some indiscretion.

My Technical Drawing teacher had a habit of ordering a misbehaving boy (TD was a boys-only subject) to the front of the class, making them bend over and whacking them with a large wooden T square kept for the purpose.

On one occasion, my Social Science teacher caught me drumming my fingers on my folder, to his great annoyance. He made me stand on my desk to demonstrate my drumming technique to the class. When I pointed out that I couldn’t hold a folder and drum at the same time, I was sent to stand in the hallway and given detention.

Violent bullying among the students was rife. Large groups of boys – and not a few girls – would gather after school to cheer on the beating of unfortunate victims. These weren’t fights, they were beatings.

I only avoided several beatings by being friends with a strong boy who knew karate. On one occasion, he dismantled two bullies at once and our small group of friends was rarely bothered again.

But I still had to walk home from school, and found myself too often in a fistfight.

My father had been a boxer and tried to teach me, but these were not Marquess of Queensberry bouts. I found my best tactic when unable to avoid confrontation was to go ballistic, use my height and reach to inflict as much damage as I could.

I’d stab my fingers into my assailant’s eyes, kick them in the balls, bite and scratch whatever I could reach and punch them in the throat. Anything that would make them stop.

And I mean “stop”. I would keep fighting until they stopped moving. Several times, I had to be pulled off boys who had long stopped fighting. I was known to not fight “fair”, which suited me just fine.

For my Year 9 school photo, I had to turn my head to three quarter profile rather than the traditional front-on shot, to hide somewhat a still very visible black eye.

Not surprisingly, this affected my attitude to school and to my education. I found reasons to stay home “sick”, and frequently wagged school.

I didn’t want to go to a place where I felt under constant threat, and I didn’t want to learn from teachers who didn’t care how well or poorly I did.

I was truly astonished then when, at the end of Year 10, my English teacher took me and another boy for a walk to tell us he thought we had great academic potential and encourage us to go on to university.

I think I was most surprised that this old, mean man had never in the preceding year appeared to show the slightest interest in me nor given me any indication of this assessment.

The fact is, my academic results slid precipitously during my four years at Claremont High. I did pass my School Certificate, enough to get me into matriculation college, but I’d come a long way down from my outstanding achievements at Abbotsfield.

I don’t recall any opportunity or inclination to pursue drama at Claremont High. If it had ever come up, I certainly would not have made myself a target for even more bullying.

On the other hand, I did elect in Year 9 to join the first group of boys allowed to do Cookery. Somehow, this wasn’t regarded as a sissy subject, probably because several of the most loutish boys saw it as a chance to slack off.

Cookery was part of Home Economics, but boys couldn’t undertake the other component, Sewing – just as girls that year were for the first time allowed to study Woodwork but not Metalwork.

In any case, the louts soon fell away or were banished, and the four remaining boys found a new world of learning on Tuesday afternoons: creative, constructive, meaningful – and tasty.

I learned to make pizzas, pavlovas, roasts, stews, salads – and they probably saved my sanity. My oldest brother was a chef, and I began to think seriously about following that path.

I remember talking to my parents about whether to go to matric and head toward teaching as my other two brothers had done before me, or look for a cooking apprenticeship. I did choose matric, but I never lost my interest in cooking.

Either way, at least I was out of Claremont High School.

The Tasmanian secondary public education system is based on students undertaking Years 7-10 at a high school, then moving to a separate institution to study for their Higher School Certificate and possible matriculation into university.

At matric, students don’t wear school uniforms, they study a mix of required and elective subjects and they mingle with students from many other public high schools.

Private schools have a different system, keeping their students at the same school and in the same uniform for Years 11 and 12.

Only a handful of Claremont High students went on to matric. In fact, a high percentage had left by Year 9 to take up apprenticeships or full-time jobs.

At the time, there were two public matriculation colleges in Hobart: Hobart Matric and Elizabeth Matric. My brother Harry had gone to Cosgrove High School and so was in the catchment area for Elizabeth Matric. I, however, having attended Claremont High, would, like my brother Andy and sister Yulia, go to Hobart Matric.

It was well known that one could take two years to study for a Higher School Certificate. Somehow, I interpreted this to mean that I could bludge my way through first year and then knuckle down in my second.

This turned out to be a serious misapprehension on my part. I spent 1975 discovering a number of things that changed my life: smoking dope, playing guitar, having sex and, of all things, surfing.

Don’t ask me how or why a 14 year old who couldn’t even swim ended up going to Clifton Beach during school hours to catch waves. But, there you go (and thank god for leg-ropes).

I wasn’t absent enough to get into real trouble but I really didn’t pay much attention while I was in class. The upshot was that when exam time came around, my results were terrible.

In fact, I failed every subject except Dutch, and even that was bare pass. But no worries, I’d just recover in second year, right?

Well, it turned out I had to plead a case to be allowed to return for my second year. I’m pretty sure that but for some strong advocacy from my Dutch teacher, my Speech & Drama teacher, my English Lit teacher (who was a friend of brother Harry) and my Ancient History teacher (who was Harry’s brother-in-law), I would have been shown the door.

I was allowed back in, and in 1976 I set about rediscovering my academic abilities. I did keep up the dope, guitar, and sex but I put surfing behind me.

The previous year, I had also been entranced by a visit from an early version of the Salamanca Theatre Company with their school show “I Must Have One of My Own, Antonio”, which was all about gender equality.

This was my first exposure to theatre-in-education. It had a profound effect on me.

In second year matric, I not only studied hard – to the relief of the teachers who’d stood up for me – but I became engaged in school-based extracurricular activities, including writing for the school newspaper and acting in school plays.

For the former, I was shy enough to write at first anonymously and then under a pen-name, but I was surprised to find my articles were quite popular, such as when I wrote about Tasmania’s archaic legal system (flogging was outlawed only in 1967).

For the latter, I won the lead role in the school production of “The Italian Straw Hat”, a classic French farce. I discovered a talent and a penchant for getting laughs from the audience and, significantly, a prodigious ability for learning my lines.

Fadinard is on stage for almost the entire two hours of the play and has a great deal to say. I loved it, being the centre of attention, and driving the action of the play.

That second year at Hobart Matric, I ended up with a bunch of Higher Distinctions, Distinctions and Credits, enough to me into an Arts degree at the University of Tasmania, or what turned out to be my preferred choice, following my brother Andy into a teaching course at the Tasmanian College of Advanced Education.

I’m not entirely sure how, given that Andy is five years older than me, but somehow I ended up just two years behind him at TCAE. As the youngest of five kids, I’d become used to the label of the younger brother of “Julia” or “Andrew”.

I was 16 when I started my tertiary education, and in hindsight it might have been wiser if I’d taken a gap year. Yes, I’d rekindled an ability to study and, indeed, a love of learning in my second year at Hobart Matric but I suspect I lacked the maturity for the serious study required to become a teacher.

But that’s another post.

Oh yes, I remember it well. You were an excellent Fadinard, pony tail and all! And yes, CHS was bloody awful, where anyone with any ambition, talent or desire had it physically and emotionally beaten out of them!

The reason we were at TCAE at the same time was that I had started an Economics degree at Uni, which I had to abandon for lack of funds – Prof Brown went out of his way to keep me in there but travel from Claremont to Sandy Bay proved unworkable. So after a stint in the PS, I buggered off to Europe for a while instead. I chose TCAE for the Drama rather than the teaching part – as did you! Not only were we in plays together, I directed you there in one, with Billy Briggs, I think.

Ah, that explains it. And, yes, you directed me and Bill (and Bob Scandrett, Terry Slater, and Carl Lawton) in “Me Mackenna”. I felt privileged. And the pantos were great fun.